So, I did a batch at the Recurse Center earlier this year. My main goal going into the batch was to work on some performance-based software engineering, and to learn more about low-level systems stuff. Knowing no Rust, and wanting to deepen my knowledge in database systems, I spontaneously arrived on this as a project at day one.

I have long postponed writing some coherent rendition of all I learned through this period, and I have decided to just bite the bullet and write about my progress anyways, months after basically abandoning (not having time for) the project.

Please do check out the Source Code.

Motivation

I have already laid bare most of my motivation for embarking on this project. Good excuse to learn Rust, learn about database systems and query languages, learn about performance optimization, opportunity to do something interesting and stupid at the same time, could lead to the opportunity of learning about distributed systems, learn about performnace optimization.

I also wanted to learn more about systems programming, and working on the database storage engine really helped build my capacity in that area. I always felt my SQL was weak since I hardly ever wrote any, using ORMs instead, and most resources I consumed on DB optimizations didn’t stick either, so I saw this as the perfect growth opportunity for both.

I felt partly the same for the contents of DDIA, add while my toy project hasn’t yet reached the stage of caring about concepts such as ACID, or MVCC, or even simple transactions or replication setup yet, I hope I get to that point eventually.

Dont fly in blind ( some database prerequisites)

While writing this, it became clear to me that some concepts would not be easily obvious without some background. This should contain the core things required to breeze through the rest of this article. I have Andy Pavlo’s Database Systems and Advanced Database Systems to thank for 99% of all I have learnt about database internals. While I would love to just paste the copious notes I have taken from the course, I realize that really doesn’t fit here, so, take some time to go through the course if you haven’t, its more than worth it.

Intro to Database Systems - Andy Pavlo

Advanced Database Systems - Andy Pavlo

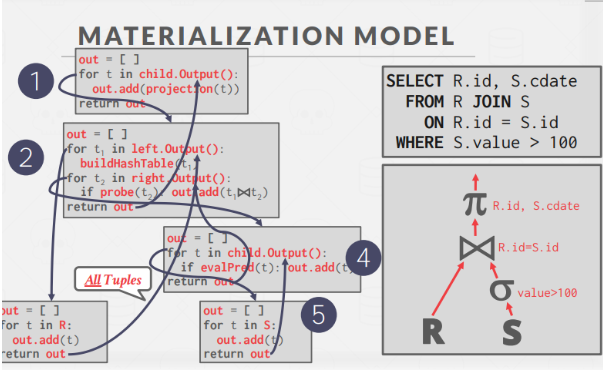

Representation of a Database Query (the DB syntax tree)

The main mental representation I would say to keep in your head while reading this article is that of the query syntax tree. I am not going to take the time to explain it, but I will leave an example here, it should make reading the rest of the article much easier.

What do I mean by Polymorphic?

One of the key goals of this project was to create a database engine that could handle different data models seamlessly. That’s where the “polymorphic” comes in. This engine isn’t limited to just relational tables in either row or columnar storage formats. It can also handle document-oriented data, similar to what you’d find in MongoDB.

This flexibility is achieved through a few key design choices:

-

Unified Data Representation : The core of the engine uses a flexible record structure that can represent both relational tuples and document-like key-value pairs. This allows for a common underlying representation regardless of the data model used, up to the table and storage levels, where implementations differ for performance gains.

-

Pluggable Storage: The storage engine supports different table types optimized for relational and document data. This means you can choose the most efficient storage strategy based on your data’s characteristics.

-

Adaptable Query Language: The custom query language I developed allows you to work with both relational and document data using the same syntax. This means you can perform joins, filters, and aggregations across different data models without switching languages or paradigms.

Essentially, this polymorphic approach allows you to mix and match data models within the same database. You could have some data stored in traditional relational tables, while other parts of your data leverage the flexibility of a document store. This opens up interesting possibilities for data organization and querying.

For example, you could store customer information in a relational table for structured data like names and addresses, but use a document model to store their order history, which might have more variability. Then, your query language allows you to easily join these two different representations and analyze purchasing patterns across your customer base. To optimize for something like OLAP(Online Analytical Processing) operations, you can also decide to store your table in a columnar storage format, which basically splits different columns of your db rows into different pages, to optimize fetching for field selective queries, aggregations, and table compression.

Language Design

Since I had a limited timeline to work on this project (about 6 weeks), I wanted to get it going with as little hiccups as possible. I’d already followed the first half of the great Crafting Interpreters book in C++, so a recursive descent parser felt like the fastest and most flexible way to get my ideas down. I hadn’t settled for a query language style at this point, but since I knew I was going to have to at least merge features from NoSQL and SQL, and given that I didn’t see the ordering of SQL statements as logical (as at then), or its parsing mechanism as flexible, the RDP was the best way for me. I was able to get it going in about a week, and it was extremely easy to adapt new features as I developed my scope.

I wrote and developed a language grammar while implementing the parser. This is what I came up with:

program => *declaration EOF

declaration => varDecl | statement

varDecl => "let" IDENTIFIER ( "=" data_expr) ";"

statement => data_expr ";"

data_expr => data_call | data_call ( ‘JOIN’ | ‘LJOIN’’) data_call ‘ON’ expr

data_call => variable | data_source(“.”method(arguments?))

method => filter | groupby | orderby | limit | offset | max | min | sum | count | select |

//arg restrictions

offset -> number ; limit -> number

orderby ATTRIBUTE

groupby ATTRIBUTE

filter lambda_expr

select (ATTRIBUTE)*

select_distinct (ATTRIBUTE)*

ATTRIBUTE => IDENTIFIER(‘.’IDENTIFIER)

lambda_expr => ‘|ATTRIBUTE|’ expr

expr => logic_or

logic_or → logic_and ( "or" logic_and )*

logic_and → equality ( "and" equality )*

equality → comparison ( ( "!=" | "==" ) comparison )*

comparison → term ( ( ">" | ">=" | "<" | "<=" ) term )*

term → factor ( ( "-" | "+" ) factor )*

factor → unary ( ( "/" | "*" ) unary )*

unary → ( "!" | "-" ) unary | primary

primary → "true" | "false" | "null" |

| NUMBER | STRING | IDENTIFIER | ATTRIBUTE ;

Most things would look familiar for any language implementation, such as the build-up of primary expressions, and the definition of a program and a statement. The main changes exist in the definitions of data expressions and data calls, an the methods which they accept. Data expressisons are basically the glue of a query syntax tree, allowing us to perform join operations on databases that have had predicates and other operations applied to them, bringing them into one stream for further processing. Data calls, are what they are named, expressions that call some table from some database and wrap methods around it until it is in a state ready for the data expression.

In my effort to make scripting tenable and replace my verbose tests, I hacked together some functionality for schema definition which I did not add to the grammar.

Here is an example program using this language

// Setup db and tables

dbs.create_db('test_db');

dbs.create_table('test_db' ,'test_table', 'DOCUMENT', 'ROW');

//schema definition

dbs.create_table('test_db' ,'test_rtable', 'RELATIONAL', 'ROW', '{

'name': 'string(50)',

'balance': ['numeric', true],

'pob': 'string',

'active': 'boolean'

}');

//insert values

dbs.insert('test_db', 'test_table', '{

'name': 'John Doe',

'age': 30.0,

'city': 'New York',

'address': {

'street': '123 Main St',

'zip': '10001'

},

'phone_numbers': [

'123-456-7890',

'987-654-3210'

]

}');

dbs.insert('test_db', 'test_table', '{

'name': 'Jane Smith',

'age': 25.0,

'city': 'London',

'address': {

'street': '456 High St',

'zip': 'SW1A 1AA'

},

'phone_numbers': [

'020-1234-5678'

],

'employment': {

'company': 'Acme Inc.',

'position': 'Software Engineer',

'start_date': {

'year': 2022.0,

'month': 1.0

}

}

}');

dbs.insert('test_db', 'test_rtable', '{

'name': 'Jane Smith',

'balance': '2502034304.2332',

'pob': 'London',

'active': true

}');

dbs.insert('test_db', 'test_rtable', '{

'name': 'John Doe',

'balance': '450.2332',

'pob': 'New York',

'active': false

}');

//actual dataflow

let x = dbs.test_db.test_table.offset(0);

let y = dbs.test_db.test_rtable.offset(0);

let z = x LJOIN y ON name=name;

z.limit(10);

As you can see from this code example, though not exhaustive, writing a query maps very nicely to constructing that syntax tree in your head, you can imagine the data flowing from the data calls to the expressions where they are joined, and then out again. This is what I always wanted, and I believe there are some query languages like this worth checking out.

Language Implementation

The implementation of the language itself was not a tedious task Learning how to deal with Rust was the main issue, given I did not go through the Rust book or any other prerequisties. I fell in love with rust-analyzer, but it turns out I didn’t even unlock its full potential at this time ( and I am still yet to). I was also very grateful for the package support provided and the ease of writing and running tests as compared to C++.

I’m just going to go through the main sections of the language implementation now.

Tokenization? Pretty straightforward.

Parsing? Not too exciting, just followed the grammar I defined.

I initially planned to implement a type checker, but I found it easier to handle type checking during the interpretation stage. This might change in the future, but I didn’t want to add another layer of complexity. The AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) also turned out to be more trouble than it was worth. I think the typechecker will be useful for very heavy operations that might fail, and would save a lot of time preventing transaction rollbacks due to issues that could have been detected statically.

Interpreter Design

My goal was to create an intermediate representation that would map well with the syntax tree, so I could run some performance based rearrangement optimizations before passing down to a query executor. I was able to do this, but it turned out to be that this IR was only serving to make my approach more inflexible, and I scrapped it. I had already created custom RecordIterator and Predicate structs which kept track of constraints for DataCall expressions, and I settled on some dynamic closure based interpreter form which made it so I could pass down these

predicates to the lowest data fetching operations, somewhat eliminating the need for an AST.

Now, the use of a closure based interpreter, while kind of weird and cool, is probably too informal and more inefficient than it has any business being, but I’m having a ton of fun with it, so I will keep tinkering on it. You can check it out here.

The core idea behind this interpreter is that in dataflow languages, later operations depend on earlier ones and on variables. Variables can be easily substituted and can represent either data calls or data expressions. Essentially, we end up with a query tree.

So, I started from the root (the last statement) and recursively unwrapped the variables into their simplest forms. This resulted in a system where data is essentially “pushed up” the tree, with each parent node processing the data from its child nodes.

It worked! I was really excited to see it in action. However, Rust and I had some serious disagreements about memory management. I ended up using Box::leak for my closures, as I didn’t want to deal with the potential lifetime hell.

AST

One of the main goals of the AST implementation is optimization. While I haven’t fully explored this yet, I have some ideas:

-

Predicate pushdown

This involves having aRecordIteratorattached to eachDataCallandDataExprwith a Predicate operator that can be algebraically combined with its parents. So all it would take is an initial pass for the root nodes to have the predicates optimally set. -

Tree refactoring

This would involve rearranging the query tree to prioritize operations that filter out data early on. For example, performing select operations before joins can significantly reduce the amount of data processed.

Storage engine

The storage engine is where the real work happens. It’s built on a few key components:

- Simple Record Structures : Basic data structures to represent different data types.

- Supported Data Types : Support for both relational and document databases.

- Table Types : Definitions for four different table types: RelationalRows, DocumentRows, RelationalColumn, and DocumentColumn.

- Serialization/Deserialization : Mechanisms for serializing and deserializing page blocks (custom for relational databases and using BSON for document databases).

At the core, you have a multi-file pager, a page cache, and B+ tree indexes for efficient data retrieval.

The boring stuff?

On the client-side, I implemented a basic TCP server and client. This allows me to send scripts to the database server for execution. The pager has read-write locks in place, but I haven’t implemented any other concurrency handlers yet.

There’s also a bunch of Rc<RefCell<T>>’s spammed everywhere for the pager and pages, for when proper concurrency will be implemented.

Sidenotes

Why I like the dataflow style

The benefit is that unlike in SQL, you dont have to think about how different operations are structured weirdly. Instead, here you can just chain operations, and compose simple statements that lead from one another. the assumption is that everything written sequentially knows how to reference variables that were defined before, and the answer flows from the root data call to all the data expressions in-between and finally to your specified output. So once you can imagine the tree of operations you desire, youve already constructed your query.